How Biomarkers Help Diagnose Dementia

On this page:

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of what’s happening in the body. These can be found in blood, other body fluids, organs, and tissues. Some can even be measured digitally. Biomarkers can help doctors and researchers track healthy processes, diagnose diseases and other health conditions, monitor responses to medication, and identify health risks in a person. For example, an increased level of cholesterol in the blood is a biomarker for heart attack risk.

Before the early 2000s, the only sure way to know whether a person had Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia was after death through autopsy. But thanks to advances in research, tests are now available to help doctors and researchers see biomarkers associated with dementia in a living person.

-

Clinical trials on dementia biomarkers

Volunteers are needed for clinical trials that are exploring new ways to detect dementia early. By joining one of these studies, you may learn more about the biological signs of dementia and contribute useful information to help diagnose and treat dementia.

The different types of biomarkers for dementia detection and diagnosis are outlined below. When combined with other tests, these biomarkers can help doctors determine whether a person might have or be at risk of developing Alzheimer’s or a related dementia. However, no single test can alone diagnosis these conditions. Biomarkers are only part of a complete assessment. Read more about diagnosing dementia.

In some cases, these biomarker tests are only available through a specialty clinic or medical research facility. Physicians with expertise in this area include neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and geriatricians. Medicare and other health insurance plans may cover only certain, limited types of biomarker tests for dementia symptoms. Check with Medicare or your insurance plan to find out what’s covered.

Biomarkers are also an important part of dementia research. They help researchers detect early brain changes, better understand how risk factors are involved, identify participants who meet particular requirements for clinical trials and studies, and track participants' responses to a test drug or other intervention, such as physical exercise. The following information notes how some of these biomarkers are used for research purposes, in addition to diagnosis.

Types of biomarkers and tests

Brain imaging

Several types of brain scans enable doctors and scientists to see different factors that may help diagnose Alzheimer’s or a related dementia. Doctors also use brain scans to find evidence of other sources of damage, such as tumors or stroke, that may aid in diagnosis. Brain scans used to help diagnose dementia include CT, MRI, and PET scans.

Computerized tomography (CT)

A CT scan is a type of X-ray that uses radiation to produce images of the brain or other parts of the body. A head CT can show shrinkage of brain regions that may occur in dementia, as well as signs of other possible sources of disease, such as an infection or blood clot. To help determine if a person has dementia, a doctor might compare the size of certain brain regions to previous scans or to what would be expected for a person of the same age and size. Sometimes a CT scan is used when a person isn’t eligible for an MRI due to metal in their body, such as a pacemaker.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of body structures, including the size and shape of the brain and brain regions. Because MRI uses strong magnetic fields to obtain images, people with certain types of metal in their bodies, such as a pacemaker, surgical clips, or shrapnel, cannot undergo the procedure.

MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of body structures, including the size and shape of the brain and brain regions. Because MRI uses strong magnetic fields to obtain images, people with certain types of metal in their bodies, such as a pacemaker, surgical clips, or shrapnel, cannot undergo the procedure.

Similar to CT scans, MRIs can show whether areas of the brain have atrophied (shrunk). Repeat scans can show how a person's brain changes over time. Evidence of shrinkage may support a diagnosis of Alzheimer's or another neurodegenerative dementia but cannot indicate a specific diagnosis. MRI also provides a detailed picture of brain blood vessels. Before making a dementia diagnosis, doctors often view MRI results to rule out other causes of memory changes such as bleeding or a build-up of fluid in the brain.

In research, various types of MRI scans are used to study the structure and function of the brain in both healthy aging and in Alzheimer's disease. MRIs can also be used to monitor the safety of novel drugs and examine how treatment may affect the brain over time.

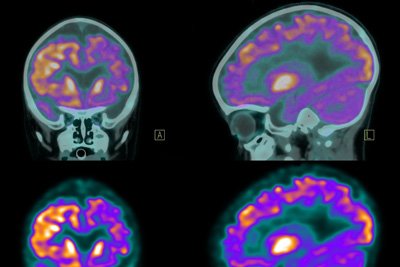

Positron emission tomography (PET)

PET uses small amounts of a radioactive substance, called a tracer, to measure specific activity — such as energy use — or a specific molecule in different brain regions. PET scans take pictures of the brain, revealing regions of normal and abnormal chemical activity. There are several types of PET scans that can help doctors diagnose dementia.

PET uses small amounts of a radioactive substance, called a tracer, to measure specific activity — such as energy use — or a specific molecule in different brain regions. PET scans take pictures of the brain, revealing regions of normal and abnormal chemical activity. There are several types of PET scans that can help doctors diagnose dementia.

- Amyloid PET scans measure abnormal deposits of a protein called beta-amyloid. Higher levels of beta-amyloid are consistent with the presence of amyloid plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease. Medical specialists may use amyloid PET imaging to help diagnose Alzheimer’s. A positive amyloid scan may mean symptoms are due to Alzheimer’s or a person is experiencing the early stages of Alzheimer’s. But it’s possible for people to have amyloid plaques and never develop the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, so doctors will consider these findings along with the results of other tests. An amyloid scan that shows just a few or no amyloid plaques usually means that Alzheimer’s is not the cause of the symptoms. These types of scans are often used in research settings to identify those at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and to test potential treatments.

- Tau PET scans detect the abnormal accumulation of the tau protein. Tau forms tangles within nerve cells in Alzheimer's disease and many other dementias. Tau PET scans may be used by doctors to monitor progression of Alzheimer's, but they are not commonly used in standard medical practice. These scans are more often used in research settings to help identify people who are at risk of developing Alzheimer’s and test potential treatments.

- Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scans measure energy use in the brain. Glucose, a type of sugar, is the primary source of energy for cells. Studies show that people with dementia often have abnormal patterns of decreased glucose use in specific areas of the brain. In clinical care, FDG PET scans may be used if a doctor strongly suspects frontotemporal dementia as opposed to Alzheimer's.

-

Understanding medical exams

To learn more about different types of imaging, check out the CT, MRI, and PET scan webpages from the NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering or download their app.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (CSF)

CSF is a clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, providing protection and insulation. CSF also supplies numerous nutrients and chemicals that help keep brain cells healthy. Proteins and other substances made by brain cells can be detected in CSF. Measuring changes in the levels of these substances can help diagnose neurological problems.

Doctors perform a lumbar puncture, also called a spinal tap, to get CSF. The most widely used CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease measure beta-amyloid 42 (the major component of amyloid plaques in the brain), tau, and phospho-tau (major components of tau tangles in the brain, which are another hallmark of Alzheimer’s).

In clinical practice, CSF biomarkers may be used to help diagnose Alzheimer's or other types of dementia. In research, CSF biomarkers are valuable tools for early detection of a neurodegenerative disease and to assess the impact of experimental medications.

Blood tests

Proteins that originate in the brain may be measured with sensitive blood tests. Levels of these proteins may change because of Alzheimer's, a stroke, or other brain disorders. These blood biomarkers have historically been less accurate than CSF biomarkers for identifying Alzheimer's and related dementias. However, thanks to more research advances, improved methods to measure these brain-derived proteins are now available. For example, it is now possible for scientists and some doctors, dependent on state-specific availability reflecting U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidelines, to order a blood test to measure levels of beta-amyloid. Several other similar tests are in development. Still, the availability of these diagnostic tests is limited: They are more common in research settings where scientists use blood biomarkers to study early detection, prevention, and the effects of potential treatments.

Proteins that originate in the brain may be measured with sensitive blood tests. Levels of these proteins may change because of Alzheimer's, a stroke, or other brain disorders. These blood biomarkers have historically been less accurate than CSF biomarkers for identifying Alzheimer's and related dementias. However, thanks to more research advances, improved methods to measure these brain-derived proteins are now available. For example, it is now possible for scientists and some doctors, dependent on state-specific availability reflecting U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidelines, to order a blood test to measure levels of beta-amyloid. Several other similar tests are in development. Still, the availability of these diagnostic tests is limited: They are more common in research settings where scientists use blood biomarkers to study early detection, prevention, and the effects of potential treatments.

Genetic testing

Genes are structures in a body's cells that are passed down from a person's birth parents. They carry information that determines a person's traits and keep the body's cells healthy. Mutations in genes can lead to diseases such as Alzheimer's. A genetic test is a type of medical test that analyzes DNA from blood or saliva to determine a person's genetic makeup. A number of genetic combinations may change the risk of developing a disease that causes dementia.

Genetic tests are not routinely used in clinical settings to diagnose or predict the risk of developing Alzheimer's or a related dementia. However, a neurologist or other medical specialist may order a genetic test in certain situations, such as when a person has an early age of onset with a strong family history of Alzheimer's or frontotemporal dementia. A genetic test is typically accompanied by genetic counseling for the person before the test and when results are received. Genetic counseling includes a discussion of the risks, benefits, and limitations of test results.

In research studies, genetic tests may be used, in addition to other assessments, to predict disease risk, help study early detection, explain disease progression, and study whether a person's genetic makeup influences the effects of a treatment.

Read more about Alzheimer's genetics and frontotemporal disorder genetics.

What is the future of biomarkers?

Advances in biomarkers during the past decade have led to exciting new findings. Researchers can now see Alzheimer's-related changes in the brain while people are alive, track the disease's onset and progression, and test the effectiveness of promising drugs and other potential treatments.

Researchers are continuing to study and develop biomarkers to improve dementia detection, diagnosis, and treatment. These may one day be used more widely in doctors' offices and other clinical settings. Learn more about biomarker advancements and biomarkers for dementia detection and research.

How you can help move biomarker research forward

The use of biomarkers is enabling scientists to make great strides in identifying potential new treatments and ways to prevent or delay dementia. These and similar advances have been possible only because of the thousands of volunteers who have participated in clinical trials and studies. Clinical trials need participants of all different ages, sexes, races, and ethnicities to ensure that study results apply to as many people as possible, and that treatments will be safe and effective for everyone who will use them. Major medical breakthroughs could not happen without the generosity of research participants who essentially become partners in these scientific discoveries.

Learn more about participating in clinical research.

To find clinical trials and studies on Alzheimer's and related dementias, visit the Alzheimers.gov Clinical Trials Finder

You may also be interested in

- Learning if you can make a difference in dementia research

- Finding out more about Alzheimer's disease genetics

- Exploring five questions to assess your risk for Alzheimer's

Sign up for e-alerts about Alzheimers.gov highlights

For more information about dementia

NIA Alzheimer’s and related Dementias Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center

800-438-4380

adear@nia.nih.gov

www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers

The NIA ADEAR Center offers information and free print publications about Alzheimer’s and related dementias for families, caregivers, and health professionals. ADEAR Center staff answer telephone, email, and written requests and make referrals to local and national resources.

Alzheimers.gov

www.alzheimers.gov

Explore the Alzheimers.gov website for information and resources on Alzheimer’s and related dementias from across the federal government.

This content is provided by the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA). NIA scientists and other experts review this content to ensure it is accurate and up to date.

Content reviewed:

January 21, 2022